Myself reflected on the big screen

I remember how chuckles would delicately swell through my body, as my brown eyes were smitten with static colors. Growing up watching cartoons that didn’t recreate the diverse scene of America submerged me in unsatisfaction. In a time of innovation, we’re progressively mindful of the negative effects on what our eyes and ears devour. No matter their religion, sexual orientation, disability or race a fictional character does not require motivation to be what they are. Just because a character represents a specific culture doesn’t imply that it must be a plot component or the only fascinating thing about their structure. A few noteworthy animated shows include minority characters, yet many still fortify stereotypes. I shouldn’t have to grasp that the only way I could identify with a black character is if they’re either a basketball player or Nike fanatic.

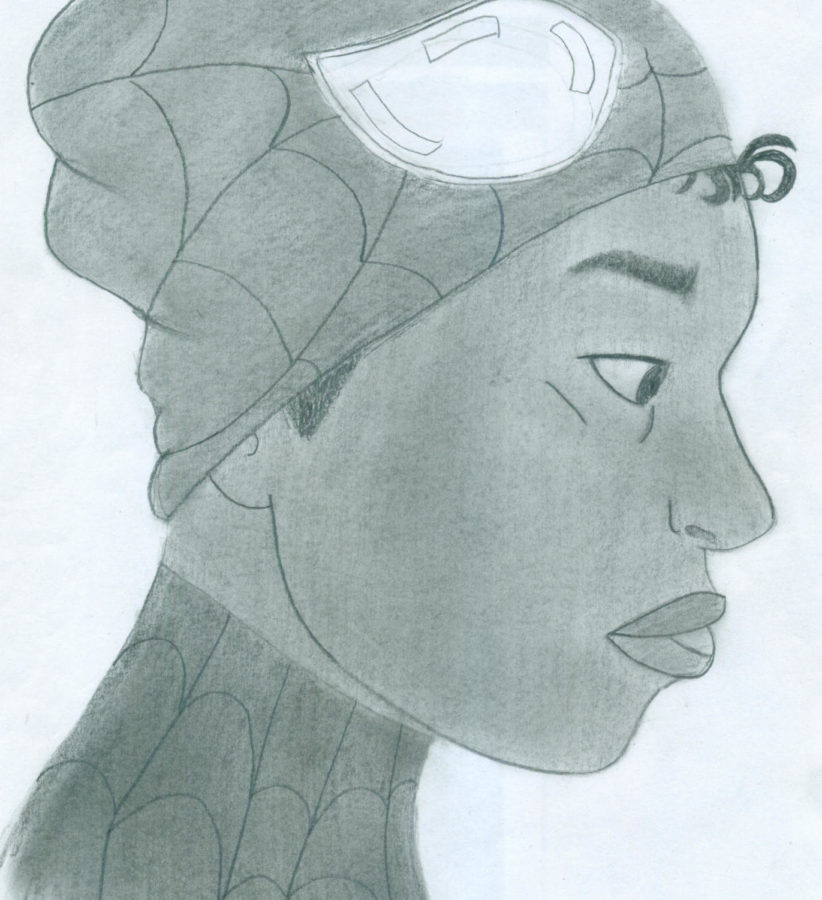

The cartoon industry clouds the realism of American society as it imitates a salad bowl of various languages and races. Representation is so narrow that even non-Marvel fans would hoard theaters to see “Black Panther” or “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” instantly while older audiences congregate to catch Disney’s children movie “Coco” in a heartbeat. During the 1970s, Boston University educator, F. Earle Barcus started distributing the after effects of studies he had conducted on children’s TV. His discoveries demonstrated huge differences between the quantities of male and female characters and between the quantities of white and non-white characters. In a recent report, Barcus examined more than 1,100 characters in twenty kids’ TV projects and found that just 42 were dark. From that point forward, analysts have discovered that the enlivened universes kids see on TV are out of match up with their genuine surroundings.

Generally, parents aspire for their kids to be ‘colorblind’, meaning to ignore the social construct of race. Nevertheless, racial features don’t impair children’s comprehension of distinction. Research has supported the significance for kids to see characters who resemble themselves and their families. Different hair textures, voices, clothes and skin tone is apparent. Media distortions of minorities can cause disarray about parts of their personality among children of these groups. In my younger years, I didn’t process it as “Hey! There’s a black character!” I recognized them as they were, not a political statement, not a revolutionary but rather a character, a person.

African-Americans represent an estimated 13.3 percent of the U.S. population. Meanwhile, Hispanic or Latinos make up 17.8 percent of the population. Protagonists like Asian-American, Jake Long from Disney’s “American Dragon” and African American, Craig Williams from Cartoon Network’s “Craig of the Creek” rebut the stereotypes that persist in both how characters are drawn and how they talk. African-American, Penny Proud from Disney’s “The Proud Family”, Mexican/Puerto Rican Maya & Miguel from PBS’ “Maya & Miguel” or even Dora Márquez from “Dora the Explorer” rebut each milked joke. Children need to see the other side of the stereotypes because everyone deserves representation.

Of course, with so many different personas, how can you begin to replicate it? That’s the true beauty of design, the accessibility to endless different stories. Minority representation has improved in recent years to where I’m not restrained to counting on one hand how many ethnic characters I could name. But if progression fades, all we’ll be able to think about is cliché, all we’ll see is cliché, until ultimately, all we’ll create is cliché.