Women in engineering: evoking the movement

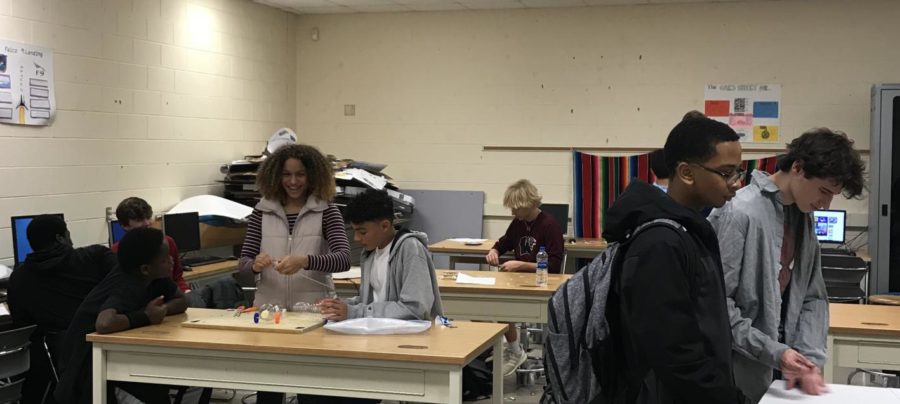

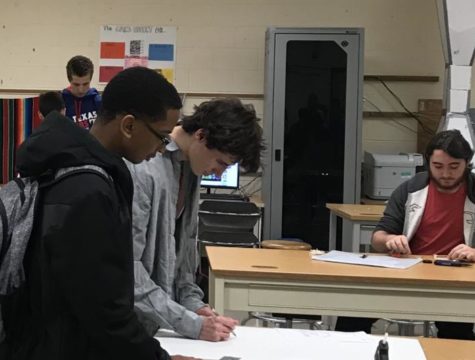

Students in Mrs. Richardson’s Technology, Engineering and Design class collaborate on a project.

As the college application season progresses, high school seniors across the nation consider their intended majors. In 2016—out of 20 million high school students—over a million pursued engineering while enrolled in postsecondary institutions, according to the Department of Education. Roughly 80 percent of them were men. Still, compared to the 1990s, far more women today are earning undergraduate engineering degrees.

What follows is a gesture to the accomplishments of female engineers nationwide: an inspiring history that includes strides toward equality, hardships and the modern movement.

According to the Society of Women Engineers (SWE) blog, in 1876, Elizabeth Bragg became the first woman to earn an engineering degree from the University of California at Berkeley. Around the same time Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) having paved the way for sanitary engineering.

Students in Mrs. Richardson’s Technology, Engineering and Design class collaborate on a design.

Troy Eller English, SWE archivist, found that women seldom (if ever) received engineering degrees during the nineteenth century. Women were often required to sit in the back of science classes. Some schools would even deny females their degrees despite completion of the appropriate program.

Senior Corbin Reifschneider, prospective biomedical engineer, discusses the historical norms surrounding engineering.

“Men have always dominated careers in math and science, especially because mechanical [and] civil engineering [are] more construction-based,” Reifschneider said. “I think that we still haven’t come around to the idea that women can do the same things men do in [engineering].”

At the turn of the century, a new wave of female engineers surfaced. In 1918, Dorothy Hall Brophy became the first woman to receive a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the University of Michigan. A year later Edith Clarke earned her master’s degree in electrical engineering from MIT. Clarke left behind a fantastic legacy. She was the first female electrical engineer and Professor of Electrical Engineering at the University of Texas, according to InterestingEngineering.com. Later in her life, she won the SWE Achievement Award in 1954.

Jung Yu, Pre-Calculus and Calculus teacher, observed more women entering the engineering role he began with at his previous job.

“There were more females coming into the position I started with, [which was] modeling/optimization,” Yu said. “You really need that one catalyst [role model] to bring [women] in [and lead them to think], ‘this is a great opportunity regardless of gender.’”

More accomplishments proliferated in the nineteenth century. Maria Telkes obtained twenty patents on solar devices she created for MIT’s Solar Conservation Project in 1950. According to National Geographic, Chien-Shiung Wu, Chinese-American physicist, helped develop the process of breaking down uranium into isotopes while working on the Manhattan project.

Students in Mrs. Richardson’s Technology, Engineering and Design class collaborate on a project.

Junior Madison Book, interested in chemical engineering, encourages girls to enter the profession.

“[Engineering involves] a lot of critical thinking [that you may not get to do] in other fields,” Book said. “It’s just a matter of understanding how things work together.”

During the late 1700s, women were not considered to have a place in academia, let alone engineering. It wasn’t until 1972 that the number of women receiving engineering degrees in the U.S. reached one percent, the SWE blog reports. Despite their efforts, women in engineering still face marginalization. According to the Pew Research Center, women in STEM are more likely than men to report having experienced discrimination in the workplace, particularly nonequal pay or treatment as though they are incompetent.

Robyn Stanek, Advanced Placement Physics teacher, advocates for female involvement in the field.

“Girls should feel accepted by the engineering community because I think we have a lot to bring to the table,” Stanek said. “We can change the way people view females in engineering if we get more girls involved.”

The movement of women toward engineering continues to take shape. Katie Bouman, for instance, received intense recognition this year—including from news sources such as The Guardian and The New York Times—for her invention of an algorithm that led to an image of the M87 black hole.

Today, only 19 percent of engineers are women, according to SWE. The ratio of men to women receiving undergraduate engineering degrees sits at roughly four to one.

“I feel empowered by [the ratio of men to women in engineering] because I’m a part of the growing number,” Reifschneider said. “Maybe me taking this step [will] open the door for other girls.”