Climate change has been on the forefront of political discussions for many decades, sparking conversations from renewable resources to recycling. One of the biggest movements include conserving wildlife, both floral and fauna, which has led to the development of the Endangered Species Act: meant to federally protect threatened species and their habitats. Over 44,000 species around the world are threatened with extinction, and 125 species are found native in North Carolina.

The state is home to over 1,000 animal-focused non-profit organizations, including nine zoos and aquariums, nearly 200 wildlife conservation and protection organizations and 62 wildlife sanctuaries. Located in Durham, the Museum of Life and Science has an abundance of native species, ranging from northern pine snakes to black bears.

Sherry Samuels is the senior director of the animal care team at the museum, and working there for 30 years has allowed her to work with various animals. As part of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ “Saving Animals From Extinction” program, the museum houses the endangered red wolf, working with institutions across the country to raise the population and make scientific discoveries.

“We got our first red wolf back in 1992, so [for] well over 30 years we’ve been part of this group of facilities around the country that is working together to try and save the species. Right now there are about 50 institutions around the country, and we work to educate and share information with our guests who come to visit,” Samuels said. “[We have] the red wolves here for people to learn about, and to hopefully get the numbers back up within the population under human care as well as the population in the wild.”

However, the Museum of Life and Science doesn’t just care for endangered species. The institution helps give unreleasable animals a forever, or furrever, home.

“With our black bears, we tend to be a site where we can take in rescued or orphaned cubs or [older] bears,” Samuels said. “Our last two bears that have come in have been unsuccessful releases of rehabbed cubs within the state.”

The museum also has a mission to educate the local community and inspire a pursuit of science. The education team works diligently to pursue this goal, especially with the use of their animals. From summer camp programs, birthday parties and school field trips, the Museum of Life and Science uses their “ambassador animals” to educate all ages.

These animals include two chinchillas – Princess Nutmeg and Pepper – a couple of ferrets, a box turtle, a den of snakes and many more creatures of all shapes, sizes and blood types. This group is never on exhibit, only being used for these education programs and are cared for with high standards.

The institution doesn’t just educate guests, however. North Carolina State University’s veterinary students often go to the site to help perform checkups on their animals, providing the students with hands-on experience.

N.C. State’s Cathy Delano is a second year graduate student, two years away from taking the test that would make her a licensed veterinarian. She plans on pursuing medicine for small and exotic animals, and as one of the presidents for the Turtle Rescue Team at the university, she has gotten hands-on experience.

“Our mission is [conservation of North Carolina’s] native wildlife species; that includes turtles, little green anoles, amphibians, snakes and [other reptiles]. [For sick or injured species], we work on taking what we have available in our experiences and we try to help them, then get them out back to where they need to go to really conserve the population.” Delano said. “[As veterinary students,] we do have access to controlled drugs that we can use to help sedate our patients to help them, and us, feel more comfortable. We often use those for procedures that we’ll need to really get in there and have hands-on. A lot of the time, they don’t really want to hurt us and we don’t want them to hurt us, so we’re respectful of each other’s spaces.”

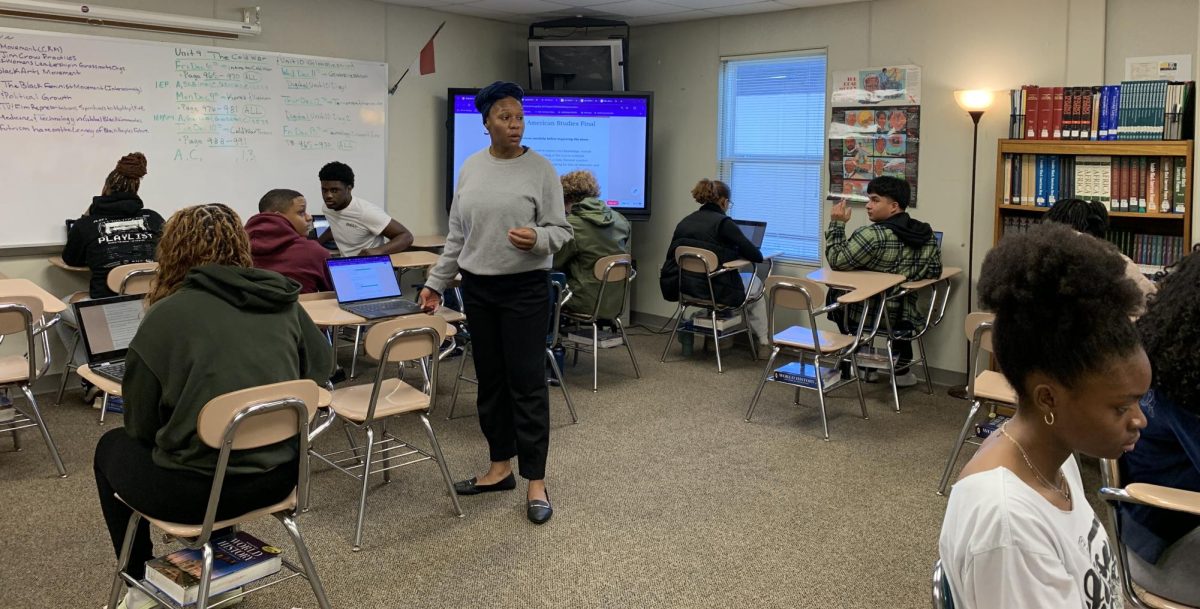

In the field of science, especially when working with animals, it’s important to be educated on the proper care these creatures need. Luckily in North Carolina, students aren’t just limited to learning how to care for native species.

The Duke Lemur Center, located in Durham, houses 13 species of lemurs and bush babies, and with a population of over 200, this location is the second most diverse population of lemurs outside of Madagascar. The center focuses entirely on non-invasive research, caring for the most threatened mammal while educating the population and working alongside students.

“A big part of our work is training the next generation of environmental stewards. We work with students both here in Durham and in Madagascar,” Erin Hecht, the Student and Volunteer Program Coordinator at the center, said. “By engaging scientists, students and the public in new discoveries and global awareness, the center promotes a deeper appreciation of biodiversity and an understanding of the power of scientific discovery.”

Their work isn’t just focused on their own lemur population, however. For over 35 years, the Duke Lemur Center has worked in Madagascar, the natural habitat of lemurs, to raise the numbers for the wild population.

“Knowing that what we are doing in Madagascar is making at least a small impact in terms of protecting forests and wildlife while also improving human lives [is very rewarding],” Charlie Welch, the Conservation Coordinator at the center, said. “What gives us the most hope for conservation and environmental protection in Madagascar is our capacity [to strengthen our] Malagasy colleagues. Although it takes time, for conservation to be sustainable it must, in the end, come from within and be supported by the Malagasy people themselves.”

For conservation to be entirely successful, people must want it to be successful. Conservation requires the work of all of us, such as using renewable resources, as well as the work of vets and conservationists, who advocate and care for the creatures who cannot advocate for themselves. Being inspired to get involved in animal conservation can come from many different forms, and luckily Wakefield High School students have a teacher who can tell them stories about his experiences.

Eric Schacht, a science teacher, worked on bison farms in multiple Mid-Western states, working on a team to care, and protect, this keystone species. Working as a high school teacher, he spreads the message of importance in both his biology and earth science classes.

“In biology we talk about diversity and biodiversity conservation. I think having biology and earth science [in high school] is [important because it helps students] get familiar with where our healthy lives come from,” Schacht said. “Everything that we use we think comes from the store but actually it comes from nature; we need nature to be healthy so that we can get everything to the store.”

For those interested in conservation, there are numerous organizations, including the ones mentioned, that you can volunteer with and get that experience. Professional conservationists and volunteers alike will learn that the most important aspect to the success of conservation is the human support system found on the teams. Whether it’s working at a veterinary clinic, a research center or an animal sanctuary, who you work with is vital to a successful work environment.

“This job is way more about people [than others think], and I work with amazing people,” Samuels said. “I get to meet and learn and see an amazing group of caregivers who support each other, who talk with guests and who care for critters that don’t speak the same language as them. The most rewarding part [of this job] is the people, as much, if not more, as the non-humans.”