To cheat…or not to cheat?

February 20, 2018

Cheating has been so common in our classrooms that, according to ETS (Educational Testing Service) “grades, rather than education, have become the major focus of many students”. But the explanation behind this changing of focus is much more complex than a student simply choosing to cheat or not to.

Nowadays, students are faced with a variety of challenges, especially inside the educational system. A North American study posted on Teen Help shows that school work is the largest source of stress on teenagers, which the study showed was 68% of stress among those interviewed.

“Certainly high school is a very stressful time for many people,” Wakefield history teacher, David Phillips said, “especially depending on those students who really wish to participate fully and to be well-rounded individuals, not only academically but to pursue extracurriculars and maybe have a job as well.”

This elevated pressure put on young students is caused mostly by the actual high competitiveness for acceptances to colleges and scholarships. According to IvyWise, general college acceptance rates dropped as low as 4.65% for the first time ever in 2017. Elite colleges like Harvard and Stanford rejected 95% of their applicants.

“The competitiveness of college nowadays,” counselor William Cummings said, “lead students to sometimes do anything at any cost when they don’t necessarily think of the consequences.”

An additional pressure that leads students to feel stress, influencing them to cheat, is the fact that just doing well academically is not enough for an applicant to be admitted into their college of choice. Many more universities now highly value the involvement of the applicant in extracurricular activities such as sports, out-of-school clubs, volunteering work and academic competitions.

Such a factor limits students’ time even more, to the point where their responsibilities may become overwhelming and seriously influence them to cheat. Senior Garret Dixon sees many of his peers put themselves in a position where the amount of time left to study and learn material becomes nearly obsolete.

“If you’re trying to take a heavy course load as well as play a sport, do clubs, do honor societies,” Dixon said, “there’s just not enough hours in the day to do all that.”

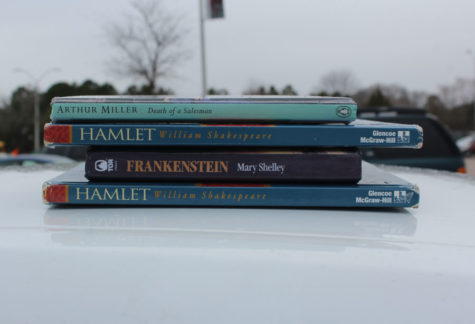

According to a survey by Donald McCabe from Rutgers University, which included 24,000 students and 70 high schools, 64% of students admitted to cheating on a test, 58% admitted to plagiarism and 95% said they participated in some form of cheating, whether it was on a test, plagiarism or copying homework.

Both Dixon as well as Camryn Jones, senior, confirmed to have known someone who cheated or seeing someone cheat. Jones shares what she thinks should change for cheating to become less common.

“ We get too caught up on the idea of getting a good grade rather than receiving a good education and I think that whole idea needs to change — Jones

But the reason why cheating is such a big deal for teachers and administrators has a deeper meaning than just grades or plagiarism.

“Certainly there are many types of pressure. But the biggest purpose of high school is to develop your character,” Phillips said. “In the long run, you’re just cheating yourself because you’re not developing yourself to your highest, fullest potential.”

High school is a transitional part of life in which people’s character is defined. Psychology teacher Stephen Holcomb explains how responsibilities and tasks influence individuals later on in life.

“If you are infiltrating yourself with scheduling, planning, and organization, for some people that might, later on in life, help,” Holcomb said. “Because they’ll be good at doing those things”.

Phillips also talks about how the high school years are decisive when referring to one’s character development.

“Your teenager years are when you’re still developing your moral compass,” Phillips said. “Teenagers are about to step into adulthood and [high school teachers] are the final step in preparing teenagers for adulthood. It is a last chance to reach them, to develop those moral standards before they’re placed among us in society as full-fledged adults.”

Psychologically speaking, it is during the teenage years that the frontal lobe of the brain is developed which, Holcomb explains, is the decision-making part of the brain. Due to that lack of development, teenagers are more motivated by the lower part of the brain, which is responsible for emotions, impulse, pleasure, and reward.

“‘I could cheat right now’ is more driving than, ‘I should not do this because this is the wrong thing’ or, ‘This could affect me in two years when I’m looking at my transcript’,” Holcomb said. “Instead of using the long-term judgment, you’re using the impulses based on right now.”