Girls can do it… right?

A fundamental need to support women in STEM

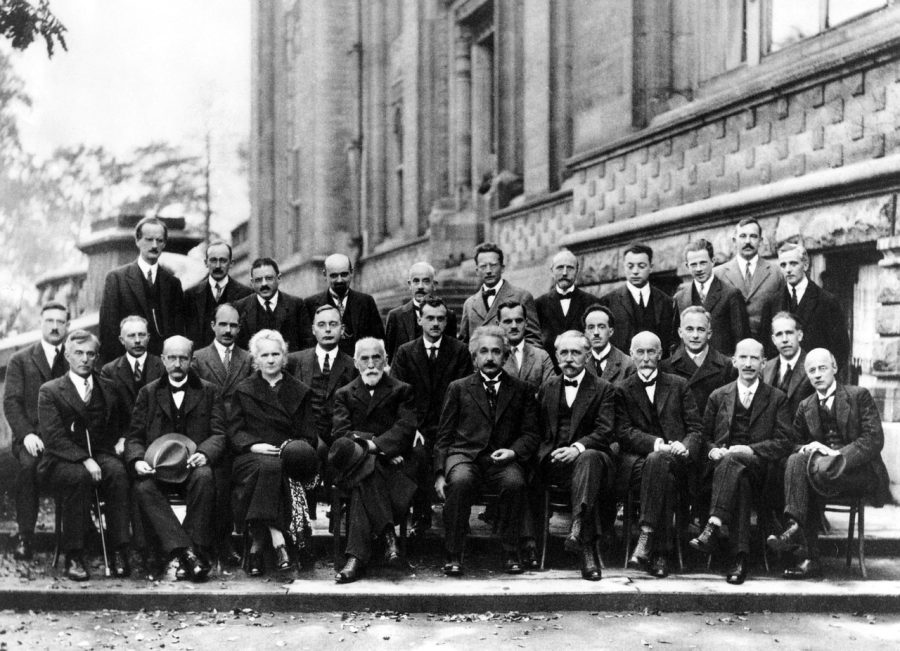

Photo Courtesy of Josh Jones from Open Culture

A group of scientists participating in the 5th Solvay Conference on Quantum Mechanics in 1927. Often noted as the “most intelligent photo ever”, Marie Curie (front row, third from left) is the only woman amongst the 29 participants.

April 21, 2022

It was International Women’s Day, and Nicole Sturgill, a vice president and technology analyst at Gartner, found herself checking her email, only to find an inbox filled with staggering low numbers representing the number of women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM).

“I kept reading about what hadn’t changed, and what still needed to change,” Sturgill said. “It was just so sad.”

There is a recognized need for girls in STEM. Women make up only 28 percent of all STEM employees, and in some of the fastest-growing and highest-paid jobs of the future, such as engineering or computer science, women contribute to only 16 percent of the workforce.

The American Association of University Women (AAUW) found the key factors contributing to the gender gap are gender stereotypes, the male-dominated culture, the lack of role models, and math anxiety.

Yet, the reservations surrounding the field aren’t ones that are introduced in the workplace, or college, or even high school. According to a survey conducted by Microsoft, girls typically lose interest in STEM subjects around the age of 11: the age where many girls begin to lose confidence in their math and science skills.

The irony is that in middle school, girls’ math and science test scores have been consistently equal to or within two points of boys.

With school systems working to promote STEM subjects at a younger age, this will increases girls’ interest and confidence in the field as they make their way through upper-level STEM courses. Forbes gave voice to the issue, stating that elementary and middle schools need to create more opportunities for children to become both familiar with and gain hands-on experience with STEM subjects, particularly those in technology and engineering.

“Schools have a major influence on whether or not someone thinks they can succeed,” Science Honor Society Vice-President Helen Ransom said.

And while schools play a pivotal role in encouraging girls to pursue STEM careers, they aren’t solely to blame for the gender gap in the workforce.

A study at the AAUW found that because fewer women study and work in STEM, this promotes the exclusive, male-dominated culture that isn’t appealing to women, resulting in less participation from women.

The lack of examples and recognition surrounding distinguished women in science will see major industries losing out on the next generation of female talent. Denise Furr is a high school chemistry teacher, and notes that it’s much easier for girls to imagine a career in STEM if they have successful examples.

“Girls lose interest in STEM careers around middle school because they don’t picture themselves in STEM careers,” Furr said. “There are not enough female role models to look up to, and girls do not have enough exposure to what STEM careers actually look like in the real world.”

Sturgill discusses the importance of females pursuing technology careers, but also emphasizes the influence that female leadership in technology has on girls.

“Until you get women in those leadership roles, [girls] will continue to steer away from STEM fields,” Sturgill said. “If you don’t have women to lift other women up and provide that perspective, the problem will just continue.”

If you don’t have women to lift other women up and provide that perspective, the problem will just continue.

— Sturgill

In addition, Microsoft found that girls are more likely to pursue a career in STEM if they think women and men will be treated equally in the workforce, and six out of 10 girls acknowledged that they would feel more confident in pursuing a STEM career if they knew men and women were equally employed.

Jennifer Adkins is a senior data scientist at SAS, one of the foremost data and analytic companies in the Research Triangle Park, as well as co-chair of the SAS Women’s Initiatives Network, which strives to inspire more young women to pursue STEM careers. SAS in particular has been supportive of the inclusion and celebration of females in science and technology, with women representing nearly 40 percent of executive positions and the global workforce.

“There are women at the top, so for a woman like me seeing women in the executive suite, it makes it look like it’s possible,” Adkins said.

Adkins acknowledges that this is not the case for all technology corporations. Today, only 20 percent of computer scientists are women, in stark contrast to the 30 percent of women who occupied those positions nearly thirty years ago.

“We need more women at the top of the technology [industry],” Adkins said.

All of this isn’t to say that women haven’t made gains – they have. In 1970, women made up only 8 percent of STEM workers compared to the current 28 percent. Still, the majority of females in STEM careers are in health-related jobs, with the minority in physical sciences, computing and engineering; fields that are the most profitable and innovative of the upcoming decades.

However, Furr recognizes a shift within her classroom.

“I have been teaching chemistry for 17 years and I have definitely noticed a trend toward females taking upper-level chemistry and those considering a career in science,” Furr said. “I think as it becomes more common, more girls will notice that it does not have to be a male-dominated field.”

But to normalize women, as well, changing the course of history, the gender gap must be eliminated. Giving girls the confidence and skills to succeed and continuing to promote female role models will ultimately be the deciding factors in the future of women in STEM.

“It’s such a rewarding field with so many possibilities,” Furr said. “I have never met a female in a STEM career who regretted it.”

Danielle Kirschner • Aug 31, 2022 at 11:56 am

Really interesting article! Great topic!@

Abby Dykes • May 3, 2022 at 8:29 am

great article!

Millie Monahan • Apr 22, 2022 at 8:30 am

this is a really amazing article!! Love your writing:)